NCEL Blog

Reconnecting Land and Wildlife Through Legislation

April 7, 2020

Overview

As our nation’s population has grown over the last century, we have freckled the natural landscape with highways, roads, and interstates so that we can travel freely.

Wildlife, however, might share a different perspective. Human development in many cases has fragmented wildlife’s migration and exploration, behaviors necessary for survival. Many species rely on migration corridors, their own ‘wildlife highways,’ for access to food, water, hibernation sites, and mates.

- Each summer elk move from river valleys to mountain meadows in search of grasses and forbs.

- Cutthroat trout and coho salmon meander upstream in spring to spawn.

- Some grizzly bears wander over 800 square miles annually.

- Monarch butterflies have them beat with 3,000 miles accumulated while fluttering between overwintering and breeding sites.

These species and countless others carve their own trails across the landscape.

Numerous roads intersect these migration corridors, impeding animals’ and even plants’ ability to move. Without access to the rest of their habitat, some are forced to inbreed, reducing both genetic- and biodiversity. For wildlife that do take the risk of crossing lanes of traffic to migrate, wildlife-vehicle collisions (WVCs) are often the unfortunate and sometimes catastrophic consequence. Add a changing climate to the mix, and all of these issues are amplified. States are taking action to try to improve this situation with strategies to conserve habitat connectivity as well as public health and safety.

What strategies have developed?

In the same way that crosswalks, bridges, and even social media have allowed humans to connect with one another and to different environments, landscape connectivity does this for wildlife, serving as the antonym to habitat fragmentation. Many states have recognized not only the value of landscape connectivity and its multitude of ecological, social, and economic benefits, but also the opportunity to reverse some of the damage done by road development and fragmentation. Recently, a tried and tested (yet still innovative!) approach has been recognizing and establishing wildlife corridors and crossing.

Think nature-friendly bridges and underpasses, and natural areas of land or water.

What is a wildlife corridor?

According to recent legislation from Colorado, the term “corridor” means a feature of the landscape or seascape that— (A) provides habitat or ecological connectivity; and (B) allows for native species movement or dispersal.

Wildlife corridors take the form of natural connected areas of land or water, and wildlife crossings are natural ‘bridges’ or ‘underpasses’ that intersect busy highways and allow wildlife to travel across or underneath without the threat of collision. The effort to plan, recognize and establish corridors has gathered strong bipartisan support and resulted in the enactment of a number of wildlife corridor and crossing measures.

These ideas, while innovative, aren’t new. The first wildlife crossing in the United States was built in Utah in the 1970s, and many are already common in Banff National Park in Canada, with 38 underpasses and 6 overpasses. Around the globe, green and blue wildlife corridor pathways have allowed connectivity for a number of species, such as crabs in Australia, elephants in Botswana, tigers between Nepal and India, and even bees in Norway.

Advantages of Landscape Connectivity

Legislators nationwide have begun to recognize the positive public health, safety, economic, and nature benefits associated with wildlife corridors. Here are just a few:

Public Health and Safety

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) estimates that there are 300,000 WVCs per year. Many collisions cause human injury or death. Wildlife crossings can help reduce these collisions by giving wildlife a safer means of crossing trafficked roads and highways.

In Utah alone, over 30,500 wildlife-vehicle collisions occurred between 1992 and 2005. Agencies found that Implementation of wildlife crossings resulted in a 40 to 90 percent decrease in WVCs. A wildlife underpass in Bend, Oregon reduced WVCs by 90%.

Biodiversity Conservation

Corridors can help maintain biological diversity, a key component of ecosystem air, water, and soil health. Landscape connectivity can promote native plant and animal species diversity and survival. Wildlife corridors can also encourage pollination. Pollinators like bees, beetles, moths, bats, and small animals can access native flowering plants in those natural areas and/or without the lethal threat of highways and vehicles. This promotes healthier plant life and agriculture, ultimately aiding in the protection of food sources.

Connected natural areas can also promote clean drinking water when a watershed or riparian area is conserved. Both wildlife overpasses and wildlife corridor areas with natural vegetation can promote plant growth and photosynthesis, an important chemical process involved in carbon sequestration. Wildlife overpasses, or natural bridges, can also reduce the urban heat island effect of highways and around nearby developed areas.

Economic Impact

The average cost of colliding with an elk is $25,319.and with a deer, it is $8,190. Nationwide, the FHWA estimates more than $8 billion in annual costs associated with wildlife-vehicle collisions, which includes emergency response, towing, repairs, medical bills and the value of the animal. Wildlife crossings can help reduce the risk of collisions in the first place, and as a result agencies are finding that they pay for themselves over time.

Wildlife corridors can boost outdoor recreation opportunities for nearby communities through the protection of wildlife species; Virginia alone generates $1.2 billion in state and local tax revenue due to activities that are dependent on healthy wildlife populations (ie: hunting, birdwatching, and fishing). Adequate culverts under roads also provide migration and habitat for fish and aquatic life, which improves recreational fishing opportunities while reducing flooding.

Policy Options

State legislators have taken several approaches to promote wildlife corridors legislation. Policies range in scope from feasibility assessments to developing state plans and providing dedicated funding. Additional options states could consider include the development of “best management practices,” private land incentives, and payment for ecosystem services.

State Activity on Wildlife Corridors in 2020

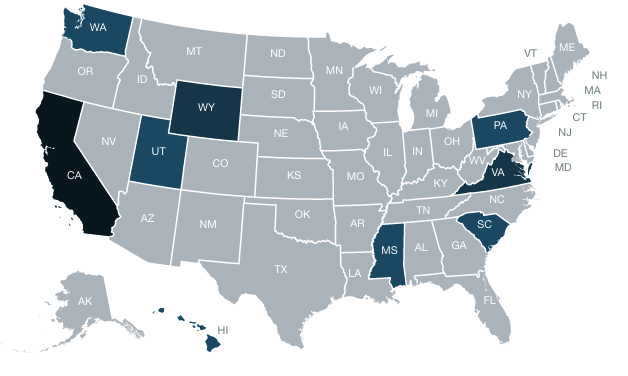

In 2020, nine states considered wildlife corridor legislation. Below are some of the bills that were considered:

- In Virginia, Senator David Marsden and Rep. David Bulova passed SB 1004/HB 1695, the Wildlife Corridor Action Plan, a bill that supports identifying wildlife corridors for future construction.

- In Utah, State Representative Mike Schultz passed HCR.13 urging continued state investment in wildlife connectivity and “acknowledging the need for the protection and restoration of migratory routes for wildlife.”

- In Pennsylvania, Representative Mary Jo Daley has introduced HR 670 to study the feasibility of establishing corridors in the state and to promote ecological connectivity.

- In California, Senator Ben Allen’s SB 45 would allocate substantial funds to protecting and restoring wildlife corridors and habitat linkages.

- In Nevada, Senator Patricia Farley published an op-ed calling for support of critical migratory habitats and corridors.

For a full list of 2020 Legislation, see here. For 2019 Legislation, see here.

Looking ahead

Studies have shown that one of the best ways to prevent biodiversity loss is to keep landscapes connected. There are a number of policy options for states to choose from, from data connectivity collection, to incorporation of data into State Wildlife Action Plans, to private land conservation incentives.

Funding for the establishment of corridors and crossings will be critical. State, federal and private partnerships will likely be essential even though connectivity pays for itself in benefits.

Keeping with the idea of connectivity, it’s also important for agencies to stay connected by communicating interagency and across state borders; wildlife don’t ascribe to political boundaries. Many best management practices also recommend building interagency partnerships that extend beyond local and state governments, looking at Tribal Nations and nonprofits who are interested in and doing similar work. Collaboration has been and will continue to be key in allowing for wildlife to move to the habitats they need to survive.